Resilience in humans has been generally defined as doing well in the face of adversity. In the psychological sciences, resilience has long been considered an individual quality. However, in the past decade, research and programming related to resilience have turned to focus on the social ecosystems that foster resilience.1 In a school setting, these social ecosystems include the school values and norms, social interactions and relationships, and community and school partnerships.

re·sil·ience

[rə'zilēəns] ·noun

ability of people, households, communities, countries, and systems to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from shocks and stresses in a manner that reduces chronic vulnerability and facilitates inclusive growth.2

This blog explores the findings of a research study on resiliency in schools in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic. It concludes that resiliency at the school level helped mediate the transition to remote learning. Some schools' resilience was strengthened by the experience.

(PDF, 14 MB)

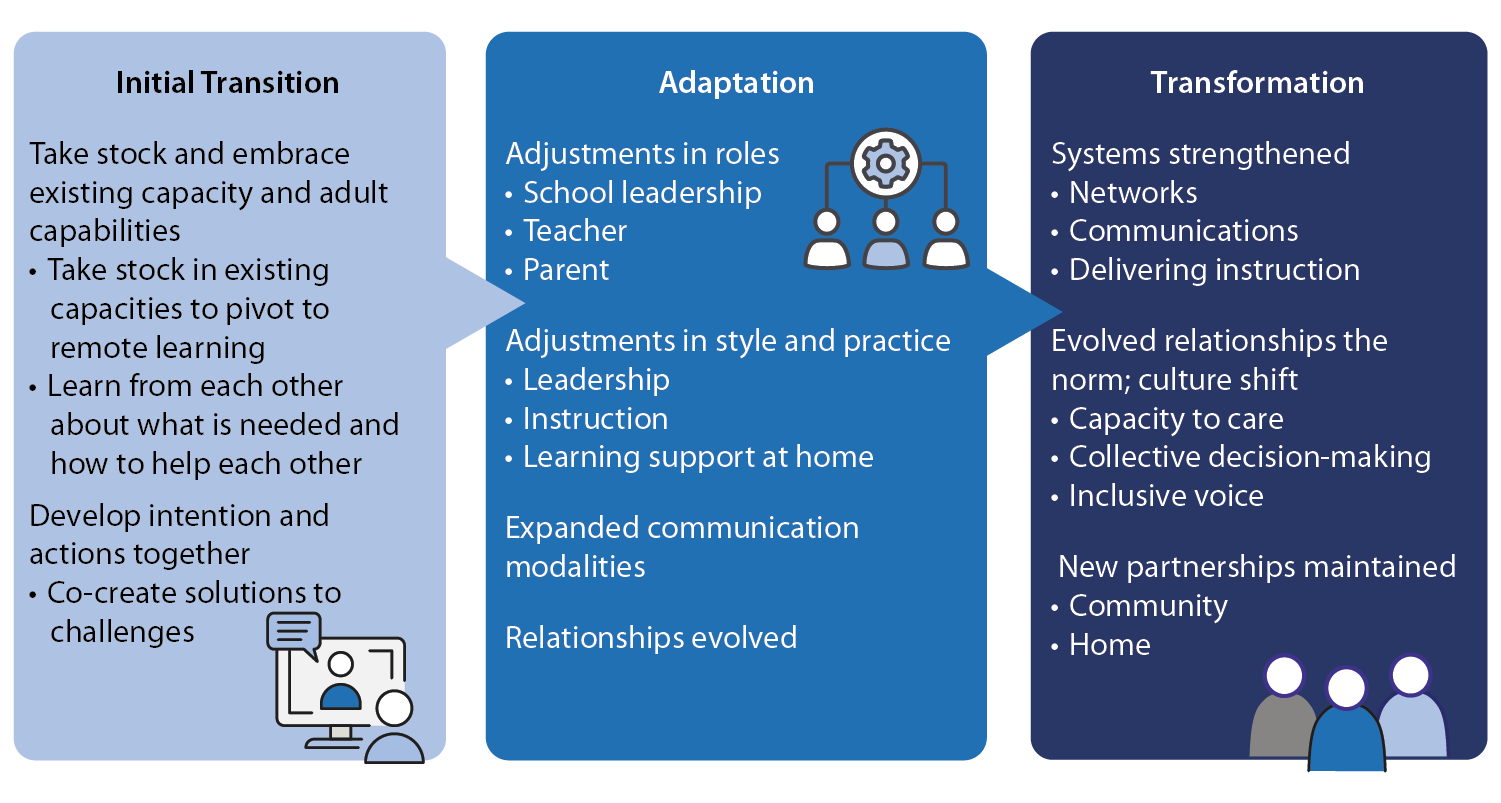

Stages of Resilience

A team of researchers followed 20 primary schools in the Philippines during the 2020-2021 school year, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. They sought to analyze the remote learning experience, and conducted case studies among a sub-sample of 10 schools. The case studies took an in-depth look at the teacher, head teacher, and family experiences during the first year of school closures to understand how early learning can best be supported in a remote learning context.

During the first year of remote learning, the 10 school communities made mixed progress in pivoting to remote learning. The researchers observed that the school communities followed a staged progression toward resilience.

All schools started an initial transition to remote learning at varying levels (poor, challenged, or smooth). Most schools then began to make adaptations (some small and some major) to support remote learning. Lastly, for a handful of schools, these adaptations were transformative, strengthening schools' resilience to meet future crises. The “stages of resilience,” observed from the Philippines study, (see Exhibit A) are consistent with the USAID resilience framework.2

Data Collection Methods

Online surveys and phone interviews were conducted at the beginning, mid-year, and at the end of the year to learn about the experiences of school heads, grade 1 and grade 3 teachers and parents from 20 schools during the first year of remote learning and how they adjusted over time.

10 schools were selected for an in-depth case study, which represented diverse school demographics, including percent indigenous persons and socioeconomic status of families.

Exhibit A. Observed Stages of Resilience

School Case Study Findings

To further analyze the data, the researchers assigned each of the 10 case study schools to 1 of 4 “Levels of Success”:

- Level 1 - Poor Initial Transition, No Adaptations (2 of 10 schools)

- Level 2 - Challenged Initial Transition, Small Adaptations (2 of 10 schools)

- Level 3 - Challenged Initial Transition, Major Adaptations (4 of 10 schools)

- Level 4 - Smooth Initial Transition, Major Adaptations (2 of 10 schools)

The levels were based on the schools' ability to transition to remote learning and their adaptive responses to the COVID-19 crisis. The characteristics of each level are described in more detail in Exhibit B. The case study was intended to explore the differential levels of success in a schools' adaptive response to remote learning. The findings provide a context for discussion and further research and were not intended to represent all schools in the Philippines.

One of the research team's major findings was that the determining factor in a school's success was the ability of school heads, teachers, and community members to adapt their roles and behaviors over time to pivot to remote learning. This enabled schools to provide continuity of learning and support the growth and well-being of learners and their families during the pandemic.

School heads became pivotal agents of resilience by supporting teachers' instruction and well-being and their ability to adapt to remote learning. Especially when school heads:

- increasingly supported and engaged with teachers;

- ensured teachers regularly met and supported each other in adapting to remote learning;

- helped teachers find pathways to connect with parents and learners; and

- mobilized community action to support households.

A school's capacity to adapt to remote learning was determined by the level to which school heads, teachers, parents, and community members interacted, learned from each other, and adapted their roles to meet the needs of parents and learners.

These findings speak to the important role that school leadership can play in promoting the capacity for continued growth and well-being during times of adversity.

Exhibit B. Characteristics of Level 1 to Level 4 schools

Conclusion

In conclusion, these findings reinforce the importance of the school ecosystem for a school's ability to adapt to a crisis, transform schools, and build education resilience to respond to future shocks. Whether that be confronting adverse events in daily life, environmental or geo-political shocks that occur locally or regionally, or a global crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Resilience in the presence of adversity is made possible through interactions between individuals and specific meaningful and accessible opportunities that are present in the school ecosystem.

Exhibit B. Characteristics of Level 1 to Level 4 schools

[1] Michael Ungar, “Chapter 2: Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience,” in The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice (New York, NY: Springer, 2011), 13–31.

[2] USAID, White Paper: Transforming Systems in Times of Adversity: Education and Resilience. (Washington, DC: 2019), 6.